About Elza

CURRICULUM VITAE

.jpg)

Elza Mayhew, 1989. Photo: Karl Spreitz

Birthplace:

Victoria, British Columbia. January 19, 1916.

Education:

B.A. University of B.C. Double Honours, French and Latin, 1936.

Studied with Jan Zach in Victoria, 1955 - 58.

M.F.A. University of Oregon, Honours Sculpture, 1963.

Travel:

Five-month world trip, 1952; one year in Japan, 1953 - 54; several visits to Europe; Yucatan, 1963.

Work in Public Collections:

: National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa: Onlookers.

: National Capital Commission: Meditation Piece, by the Rideau Canal, Ottawa.

: Confederation Centre of the Arts, Charlottetown, PEI : Column of the Sea.

: Royal British Columbia Museum: Spirit (column), Caryatid.

: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria: Demeter, Persephone, Sphinx, Board of 10.

: University of Victoria: Coast Spirit (column), Bronze Priestess.

: Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, B.C.: Guardian II.

: Brock University, St. Catharines, Ontario: Concordia (column).

Commissions (Murals, Monuments):

: 1967 B.C. Archives and Museum, Victoria. Spirit.

: 1967 Expo, Montreal. Two major commissioned works, Concordia and Meditation Piece.

: 1968 Bank of Canada, Vancouver. Bronze mural. In 1999, walled in by new owners of the building.

: 1973 Confederation Centre, Charlottetown, P.E.I. Column of the Sea, Centennial Project.

: 1988 University of Victoria, Bronze Priestess.

Exhibitions: Juried or Invited.

: 1960 Outdoor Exhibition of Sculpture, Quebec City.

: 1962 Contemporary Sculpture Show, Ottawa (Travelling).

: 1964 Sculpture Today, Dorothy Cameron Gallery, Toronto. Five Canadians.

: 1965 International Trade Fair, Tokyo. Aluminum sculpture.

: 1966 Canadian Religious Art Today, Toronto. Holy Man.

: 1967 Centennial Sculpture Exhibition, Vancouver.

: 1976 Spectrum Canada, RCA Show for the Olympic Games.

: 1978 Sculpture Canada '78, Toronto, London, Brussels, Paris.

: 1983 Contemporary Canadian Sculpture, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

: 1984 North Park Gallery, Victoria, Opening Invitational.

: 1986 EXPO 86, Vancouver. ZONG, Supplicant.

: 2009 Vision Into Reality: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria Early Years 1951 – 1973 (The Colin Graham Legacy), Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

UVic Torch, back cover, spring 2004. Photo: Vince Klassen

One-Artist Shows:

: 1960 The Point Gallery, Victoria. Also in 1962.

: 1961 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Indoor-Outdoor.

: 1961 Fine Arts Gallery, U.B.C.

: 1963 Lucien Campbell Plaza, University of Oregon, Eugene.

: 1964 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

: 1964 Venice Biennale, Canadian Pavilion.

: 1965 Dorothy Cameron Gallery, Toronto.

: 1971 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Retrospective.

: 1978 Backroom Gallery, Victoria. "Small Sculptures."

: 1979 Burnaby Art Gallery, Burnaby, B.C.

: 1980 Equinox Gallery, Vancouver.

: 1980 Albert White Gallery, Toronto.

: 1981 Wallack Gallery, Ottawa.

: 1988 Port Angeles Fine Art Centre, Washington, U.S.

: 1992 Fran Willis Gallery, Victoria. With Bob de Castro.

Awards:

: 1962 Sir Otto Beit Medal from the Royal Society of British Sculptors.

: 1967 Purchase Award, B.C. Centennial Sculpture Exhibition.

: 1989 Honorary Doctorate, Fine Arts, University of Victoria.

Memberships:

: 1974 Elected to the Royal Canadian Academy.

: 1968 - 79 Board of Directors, International Sculpture, Kansas.

: 1974 - 76 Consultant, Government of British Columbia, Committee on Art.

: 1983 - 85 Acquisitions Committee, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Unfinished work:

: Moonpiece. Height 8 ft.

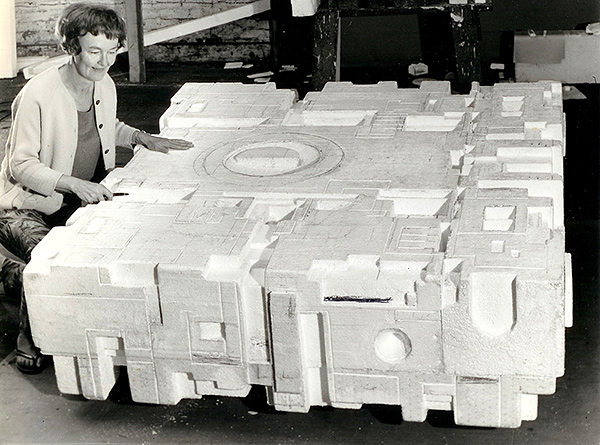

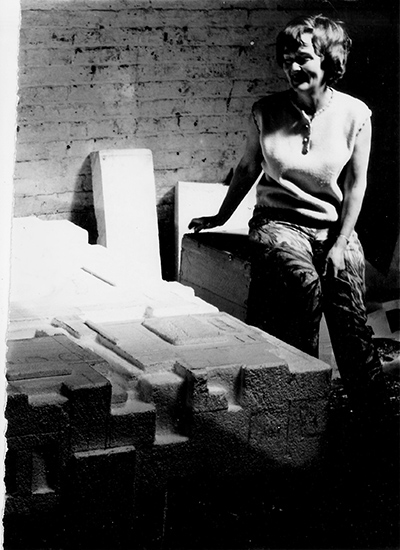

Meditation Piece styrofoam with artist. Photo: Ken McAllister.

ARTIST'S STATEMENTS

Elza’s signature, on Synthesis. Photo: Ken McAllister

Elza Mayhew: Artist’s statements and miscellaneous notes.

The artist works for many years, and makes diverse things in varying media and styles. Then he finds, if he has worked with sufficient concentration, that for the most part he is "at home" – at his most humble, unpretending, best, most honest – in one particular manner of expression. Generally, I like to carve. I think of carving every good block I see. This is a direct approach. I feel, too, the insistence of dominant horizontals and verticals within a work...

I am a slow worker, and lyrical as I may feel at the outset, I have to think a great deal about what I want to say. Many rough sketches are made. When the idea grows clear, then the forms can start to work. Nothing can be done without this search, which is both perceptual and conceptual. The work is not pre-ordained. I rarely use models. The basic concept as expressed by divisions is clear when I start. From that point on, the sculpture slowly reveals itself on many levels. It must be composed. Herein is the excitement. Any model beyond the basic simple mass divisions would impede the development of the concept...

Perhaps mine is "environmental" sculpture, rather than geometric.... I have never made anything not closely connected with the human being and his environment. Man and his longings, desires, his dwellings, the thresholds he passes over and his places of worship concern me; people, buildings, entrances through which people go in, come out; and the apprehension, the pleasure or the peace that accompanies these acts. Passages may suggest revelations of the unknown, and black holes refer possibly to far recesses of the mind.

Man's efforts to maintain the dignity of the human state have always impressed me. The rituals to which he conforms, to help maintain his position between the past and the future – these are some of the things I think about. The search brings me to forms that are strongly ritualistic, religious, meditative in essence; and to the use of a symmetry which helps express the rites by which man is able to support himself.

In the sense that the work is mainly monolithic and totemic, I am a traditionalist, dominantly concerned with the old inevitable sequence of past, present and future... [However] absorption in the monolith does not exclude an awareness of the use of form as a development of thought. Thinking today certainly is on a different level from that of Ancient Egypt, for example. It has many more facets, is much more complex. Perhaps this is why for some years I have insisted on opening up space within the volume in various ways, which is actually a denial of the monolithic character, as are the protrusions which extend out from the block. In other words, I attempt to explore the possibilities of extension of meaning in formal expression, and to this degree, my work is hand-in-glove with the developments of this century.

The unknown is the important driving force which leads man to create. The power of ambiguity in art is very great. As long as we do not know the purpose of living, to what end the human effort is directed, art can have no absolute meaning. It will manifest all man's needs, what he knows and what he does not know. It is the expression of the human, impelled by he knows not what, to an end he cannot comprehend.

Date unknown.

The more sculpture I make, the more wordless I have become. You don't think in verbal terms. I don't even think about my work anymore, I just make it.

As quoted by Frank Nowosad, "Vertical inspiration", Monday Magazine, December 1978.

I started [the sculpture Cerberus] in a naïve manner, ... things just appeared. I knew I was going to have this arch carved through the solid block, but as to a figurative image, I had no preoccupation. It just turned into a fish. Also it was not until later on that I noticed that there were steps going down the left-hand side. This must have been derived from a concept of buildings. Buildings, and people going into buildings and coming out of buildings.

As quoted by Kenneth Coutts-Smith, Rites of Passage, 1972.

Elza in the Wharf Street studio. Photo: Ken McAllister

My sculptures are very central. There are verticals and horizontals but few diagonals. They are highly structured and very architectural but they always relate to the human form.

Many societies found security for themselves and their towns in columns or archways. Totems give a terrific feeling of security and they also mark time. They tie people to their past and future and I feel that my works are likewise – markers in time and of a place.

As quoted by Frank Nowosad, Monday Magazine, December 1978.

I feel terrific things when I put a hole through a work. I am really making doorways and that is something with which I have always been fascinated. Also when I make an opening or an archway, I always have to indicate human presence and then it is usually in a relatively minute way. It generates a sensation which is absolutely overwhelming.

As quoted by Frank Nowosad, Monday Magazine, December 1978.

It perhaps does not come out enough [in your manuscript], that I was born here, and that except for travels I have always lived here, and that in spite of the limitations of the area I loved this small Island capital. I have roots in the region, and am not attracted to the international in art. I feel I belong in this place with its beaches, forests, cliffs, and the often roaring Pacific Ocean. I am lonely most other places I go.

A letter to Kenneth Coutts-Smith, c. 1972.

It is a building [Fabled City]. It is a huge architectural block. There are passages that people can go along. It is, of course, a solid piece of stone, but with those doorways you get a feeling of inner space, of the space inside the stone. You can get in there sometimes. I have to try and grasp the inner space of a dense solid block, to try and realise it. Perhaps I am trying, myself, to get inside the mineral block. I am looking for something very hidden inside, something very secret, very dark. I like secrets, you know. They are important. For things to be cherished, for things even to be true, they must be secret.

As quoted by Kenneth Coutts-Smith, c. 1972.

Art is nothing if it's not a philosophy. It's an attitude to life, it's not a thing of the moment. And it must really refer to the past and the present and the future. In other words, to take in the full scope, it must express something of the feeling of the span of life from birth to death. It's totemic, it's a generational thing, it refers to people yet to come, and to people who have passed away.

From an interview with Fernau Hall, 1978

Black Priestess, bronze cast. Photo: Morgan Price

The Black Priestess (1961) is considered to be Mayhew’s “signature piece”.

The original Priestess, in compound stone, is 40 inches in width (H: 30” x W: 40” x D: 15”).

There derived many other priestesses, in many sizes and variations as befits priestesses, from a width of 54 inches down to a half-inch, and regardless of size, the strong form always holds true. The artist’s intent was, some day, to “make the Priestess as large as a building, so people could walk through the passageways”.

Here are her pencilled working notes from 1961:

1. to have a great refinement –

in form

in proportion.

2. to be “open” –

to the space around

to the human –

3. to be the ultimate in understatement

4. perceptual

conceptual

architectural

personal

In an unpublished essay dated 1972, Kenneth Coutts-Smith wrote: “There is, in Mayhew’s work, a whole family of sculptures where a sense of a mysterious inner space, of secret chambers, is wedded to a distinct elegiac quality…. Ossip Zadkine, confronted by this piece, pointing at a depression in the surface, once remarked to Mayhew, ‘I want to be buried right there. Make it big enough for me to be buried right there’.”

ELZA MAYHEW - BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aarons, Anita, ed. Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Allied Arts Catalogue. Toronto: Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, 1968.

Amos, Robert. "Mayhew works displayed perfectly in idyllic setting". Times-Colonist, August 27, 1988.

Bishop, George. Northwest Bronze Foundry, Ferndale, Washington. Unpublished letters, 1977. Archive of Anne Mayhew.

Elza on ladder in Victoria studio. Photo: Ken McAllister

Bovey, Patricia E. A Passion for Art: The Art and Dynamics of the Limners. Sono Nis Press, Victoria, B.C., 1996.

Cameron, Dorothy. Sculpture '67. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1967. Exhibition catalogue.

Canada: XXXII Biennale di Venezia, 1964: Harold Town and Elza Mayhew. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1964. Exhibition catalogue.

Canadian Outdoor Sculpture Exhibition 1962. Ottawa: National Gallery of Canada, 1962. Exhibition catalogue.

Canadian Sculpture: Expo 67. Edited by Nathan Karczmar. Montreal: Graph, 1967. Exhibition catalogue.

Coutts-Smith, Kenneth. "Rites of Passage: the sculpture of Elza Mayhew." Unpublished essay, c. 1972. Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery Fonds, University of British Columbia. Also in archive of Anne Mayhew.

Dalsin, Melba. "Monuments to the Past, the Present and the Future: The Artistic Legacy of Elza Mayhew." Master's Thesis, University of Victoria, 2010.

Emery, Tony. "Elza Mayhew." Canadian Art, Vol. XX, No. 4, July/August 1963.

Grison, Brian. "Colin Graham and West Coast Modernism." Focus, December 2009.

Hazel, Kathryn. "The Evolving Art of Elza Mayhew." The Daily Colonist, March 11, 1973.

Howarth, Glenn. "Spirit of Timelessness." Victoria Daily Times, June 19, 1971.

Hughes, Mary Jo, Michael Morris and Barry Till. Vision Into Reality: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria Early Years, 1951-1973. Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 2009.

Hull, Roger. Intersections: The Life and Art of Jan Zach. Salem, Oregon: Hallie Ford Museum of Art, Willamette University, 2002.

Johnson, Audrey. "Creative Elsa [sic] Carves in Heroic Terms." Times-Colonist (Victoria), June 14, 1981, 29.

Litwin, Grania. "Victorian was 'closest thing to Emily Carr we ever had'." Times- Colonist (Victoria), January 15, 2004.

Madden, Aaren. "Scratching the Surface: The Sculpture of Elza Mayhew." Honours BA paper, University of Calgary, 2004.

Elza and Herbert Siebner in studio with styrofoam. Photo: Karl Spreitz.

Moir, Nikki. "Her creative talents travel the world with her." The Women's Province, Vancouver, BC, January 6, 1966.

Nowosad, Frank. "Honouring Elza Mayhew." Monday Magazine, November 23, 1989.

Nowosad, Frank. "Vertical Inspiration: The Monumental Sculpture of Elza Mayhew." Monday Magazine, December 8, 1978.

Royal Architectural Institute of Canada Allied Arts Catalogue, Vol. 2, 1968.

Sculpture Canada '78. Toronto: Sculptors Society of Canada, 1978. Exhibition catalogue.

Skelton, Robin. "Elza Mayhew: A Language for Humanity." The Malahat Review, No. 18 (April 1971): 58-91.

Skelton, Robin. "The universe unfolds in the palm of a hand." Monday Magazine, October 1992.

Tuele, Nicholas and Liane Davidson. Art in Victoria 1960-1986. Victoria: Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1986. Exhibition catalogue.

University of Victoria Alumni Quarterly, Autumn 1970.

Whittaker, Julia. "The Limners: Art in Victoria 1920-1989." Master's Thesis, University of Victoria, 1989.

Williams, Arthur. The Sculpture Reference: Contemporary Techniques, Terms, Tools, Materials, and Sculpture. Sculpture Books Publishing, Gulfport, MS, USA, 2005.

Film: Time-Markers: The Sculpture of Elza Mayhew, directed and produced by Karl Spreitz and Anne Mayhew, 1985.

Listed in Canadian Who's Who, Who's Who in American Art, 2,000 Notable American Women, The International Who's Who of Women, Who's Who in the West, Dictionary of International Biography.

Board of 28. Photo by Stanley Triggs.

SELECTED QUOTATIONS

Elza’s sculptures at the Museum [Spirit and Caryatid] create such a focal point for our garden and announce to all our visitors that this is a museum of immense importance and interest. They ennoble the museum and its approach but they also humanize it and arouse great interest and curiosity.

Prof. Jack Lohman, CBE - Chief Executive Officer, Royal BC Museum, Victoria. From an email August, 2017.

Sculptures by Elza Mayhew at the Port Angeles Fine Art Centre…. There is a classical calm. Mayhew's works are usually symmetrical, roughly geometric, at rest…. There's a peacefulness which bespeaks ancient roots. In 1988 art is often cynical, fragmented, bound up in its own psychoses. Mayhew's work stands above all that: patient, engaging, composed.

Robert Amos, "Mayhew works displayed perfectly in idyllic setting", Times-Colonist, 1988.

Board of Ten. Photo: Karl Spreitz

It is in such an unanticipated confrontation [in wild and tangled undergrowth] that Mayhew's images make their greatest impact, for the spectator is obliged to acknowledge an element of presence in the sculpture, not only the specific object's physical existence, but also a certain extra and mysterious dimension of mythic presence.

Kenneth Coutts-Smith, Rites of Passage: The Sculpture of Elza Mayhew, 1972.

The image of the Black Priestess is far from unique: Kore, Warrior, Matrix, Stele I and Stele II and many others form funerary images. Like archaic tombstones, they both lament a death and transcend that death, they stand as markers, as boundary stones at the frontiers between one world and another; they act themselves as a gateway, a point of conjunction between the material world and the invisible world.

Kenneth Coutts-Smith, Rites of Passage, 1972.

In Mayhew's case, an overall elegiac tone reflects a basically tragic view of life. Her theme of the archway, of the orifice penetrating into a mystery, is balanced by a recurrent lamentation, an elegiac statement based upon, and perhaps transcending, a personal loss and suffering.

Kenneth Coutts-Smith, Rites of Passage, 1972.

Scale is ambiguous in almost all of the work of Mayhew: a small niche is emotionally big enough for a tomb, a small opening becomes a towering processional arc de triomphe. This element would seem to have come about from the artist's method of working. Mayhew confronts, for long periods of time, a very small area of the whole sculpture.

Kenneth Coutts-Smith, Rites of Passage, 1972.

[Her work] is not didactic or analytic, but creative and synoptic. Above all, her simple columnar forms express in an entirely individual and personal way her sense of the tragedy implicit in the human condition in the twentieth century. She has chosen to express herself in a way which we can call classical … because she believes fervently in the regenerative power of absolute form.

Tony Emery, Canadian Art, 1963.

Her sculptures are almost ceremonial figures related basically to architectural forms and spaces, modern in concept yet having affinities with the past, with totemic poles, Mayan stelae, Egyptian stone sculpture, and other hieratic forms through which the artist has asserted the dignity of the human state while reminding us of the awesomeness of the workings of the macrocosm.

Colin Graham, Canada: XXXII Biennale di Venezia, 1964. Exhibition catalogue.

Elza Mayhew (1916-2004) is probably the most well-known of British Columbia's modernist sculptors. Her tall bronze or aluminium cast forms can be seen in many public spaces throughout the province. While suggesting a human-sized totem, the sculpture, "Princess," is more akin to the more 'primitive' pictographs of prehistory or Surrealism. With its softly shimmering surface, its jagged sgraffito and its thin vertical cuts that allow light to penetrate right through, "Princess" evokes the effect of shafts of sunlight sparkling between the massive trunks and branches of the tall trees of the coastal forests.

Brian Grison, Focus, December 2009.

The sculpture [Spirit ] is a labor of obsessive love. Modulation upon modulation are piled and organized into an imposing totem. That the work is vaguely figurative, with a commanding spirit, almost religious, is secondary to the unending complexity of surface modulation…. The end result is ritualistic. To run your eye up to this tower is a ceremony. For the artist the tight ritual comes from a formlessness left behind.

Glenn Howarth, Victoria Daily Times, 1971.

Elza with grinder. Photo: Ken McAllister

Elza Mayhew (1916 – 2004) is perhaps one of Canada's best known sculptors from the modernist period. She was chosen to represent Canada at the 1964 Venice Biennale with Harold Town, at Expo 67 in Montreal and at Expo 86 in Vancouver…. Her independence, her dedication to modern form, and her determination to create despite many challenges, marks Mayhew as one of a number of strong women artists…. A war widow with two children, [she] studied with Jan Zach from 1955 to 1958 and became entirely committed to her sculpture.

Michael Morris, Vision into Reality: Art Gallery of Great Victoria Early Years, 1951 - 1973, 2009.

This Saturday, Elza Mayhew, at the age of 73, will receive an honourary doctorate from the University of Victoria….

Mayhew's concerns are classical and formal, and she tends to discuss her works in terms of Western art history. Yet the most persuasive affinities are with the indigenous art of the Pacific Coast. Her methods of carving and her frequent use of the totemic form are obvious…. But I think the connections are more fundamental: they have to do with her recognition of the elemental, wild nature of this place. This is reflected in the implied stoicism of the work, the constant balance between permanence and impermanence and the sheer physical presence of each piece.

She does not acknowledge any overt influence of the culture that preceded the European settlement of the Coast, and yet she reflects, "I could never have done my work anywhere else, not Toronto, not Europe. I knew I belonged here."

Frank Nowosad, "Honouring Elza Mayhew", Monday Magazine, November 1989.

Somehow all these works, however much they allude to classical myth or to archetypal symbols, have a human warmth; they are part of life as we live it, and have always lived it. Thus, the three Maidens of Knossos stand together almost as if they were women chatting in the street; they have a kind of statuesque unconcern; they are simply themselves ….

Robin Skelton, Monday Magazine, October 1992.

Elza Mayhew was a sculptor for a very large portion of her life. She received wide recognition for her work. As time went on, however, she suffered from dementia attributed to constant exposure of expanded polystyrene fumes while using a heating (melting) iron.

Arthur Williams, The Sculpture Reference, p. 440.

Vaporized casting (lost pattern casting) Metal casting using a model of expanded polystyrene (Styrofoam*) fully encased in a foundry mold of sand products. A pouring system is attached for the flowing metal. As the hot molten metal enters, the polystyrene burns out (vaporizes), leaving a solid metal in the new cavity…

When burned, Styrofoam and other polystyrene materials give off toxic gases that can cause visual difficulty, as well as memory loss.

Arthur Williams, The Sculpture Reference, p. 461.

ARTICLES BY ANNE MAYHEW

Anne Mayhew, daughter of Elza Mayhew, is a journalist and wildlife writer who has spent other parts of her life considerably involved with her mother’s work.

She has written two family pieces for Homemakers magazine: one on her father, a pilot whose plane went down in the Indian Ocean in 1943. And the next, the “Second Wing”, on her mother, the widow, the artist, the mother.

They are made available here courtesy of the magazine.

Click for larger versions. Files may take a few minutes to completely download.

Introduction to If Words Had Wings

If Words Had Wings

The Art Of Living

Elza with stone head of Anne. Photo collage: Ken McAllister.